Welcome to Build a Better Boulevard:

a project to imagine the future of Wilkinson Boulevard.

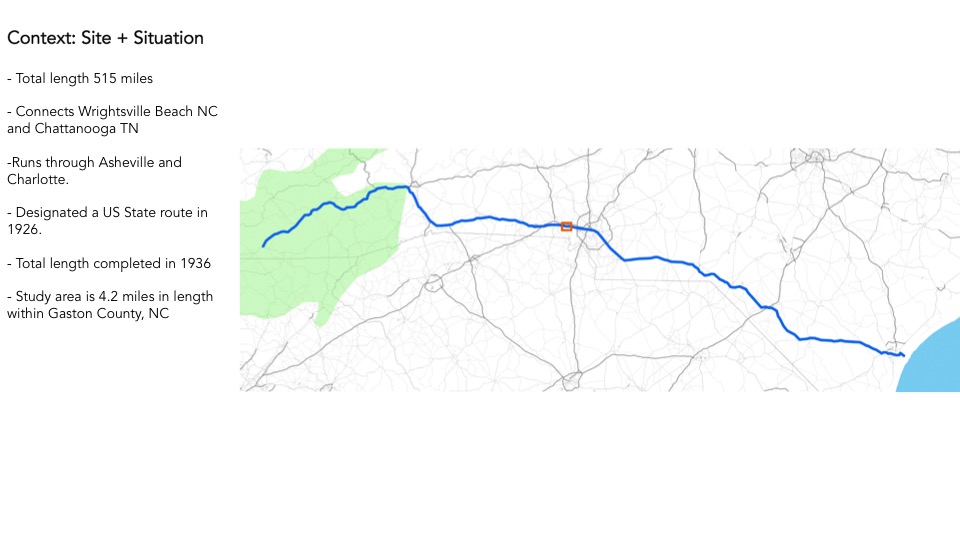

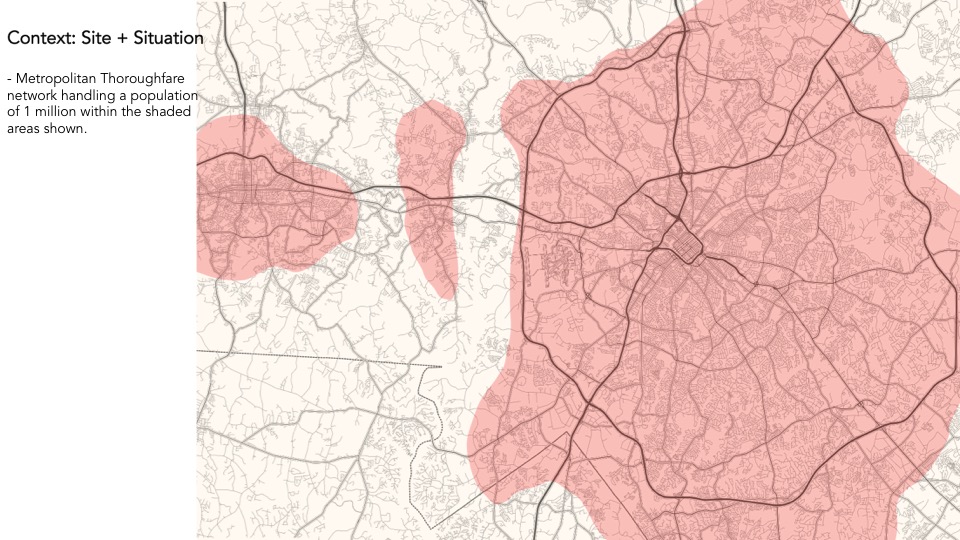

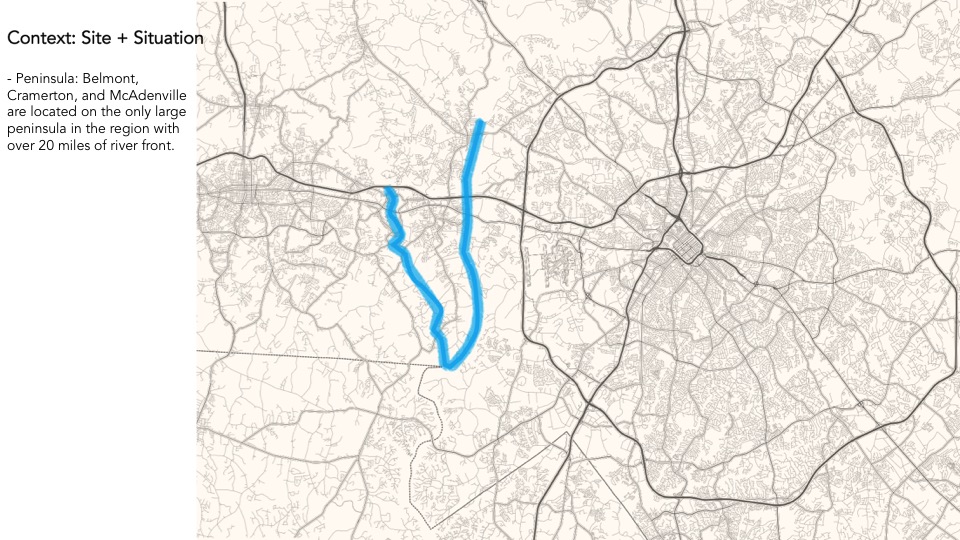

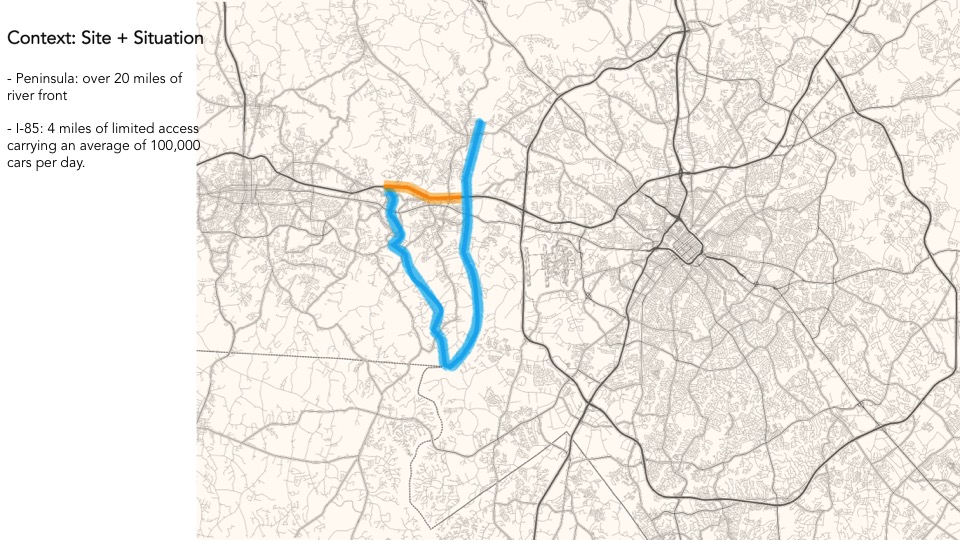

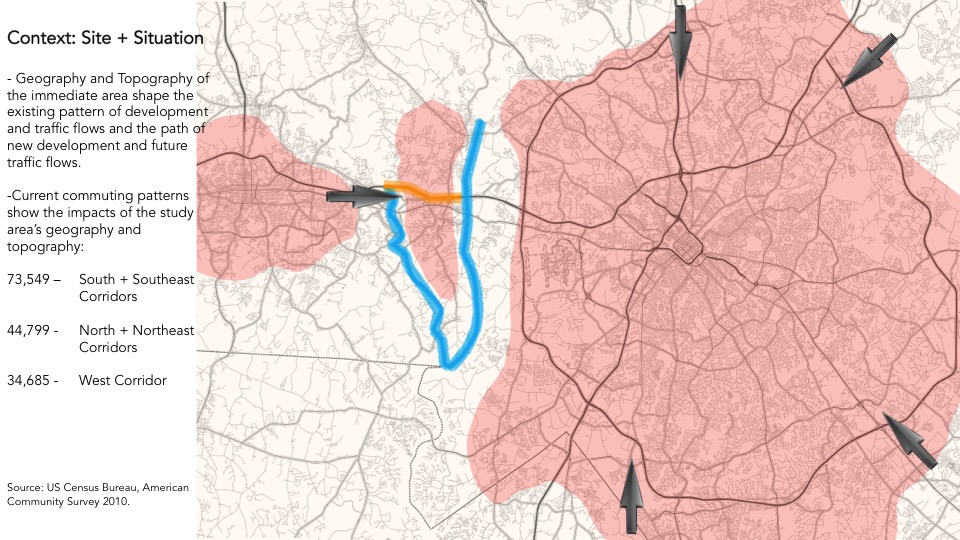

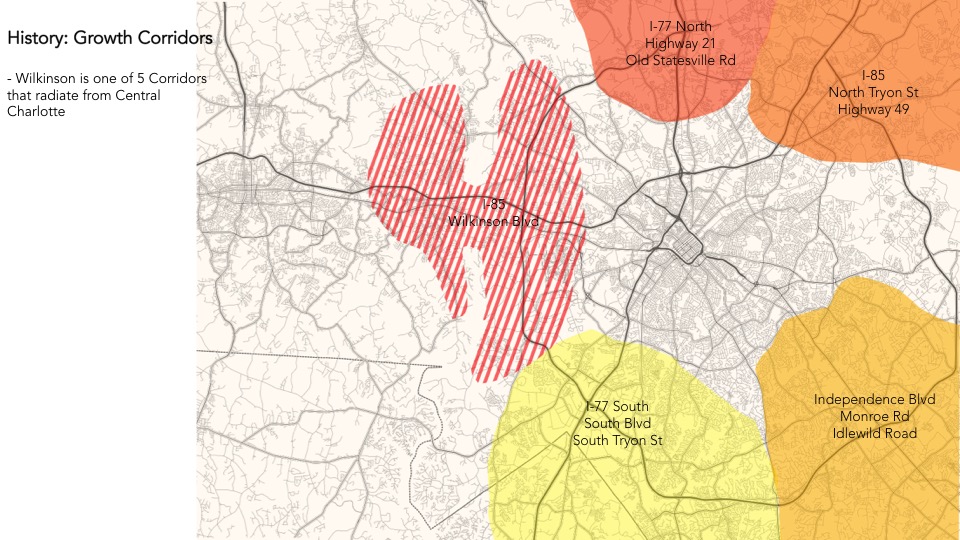

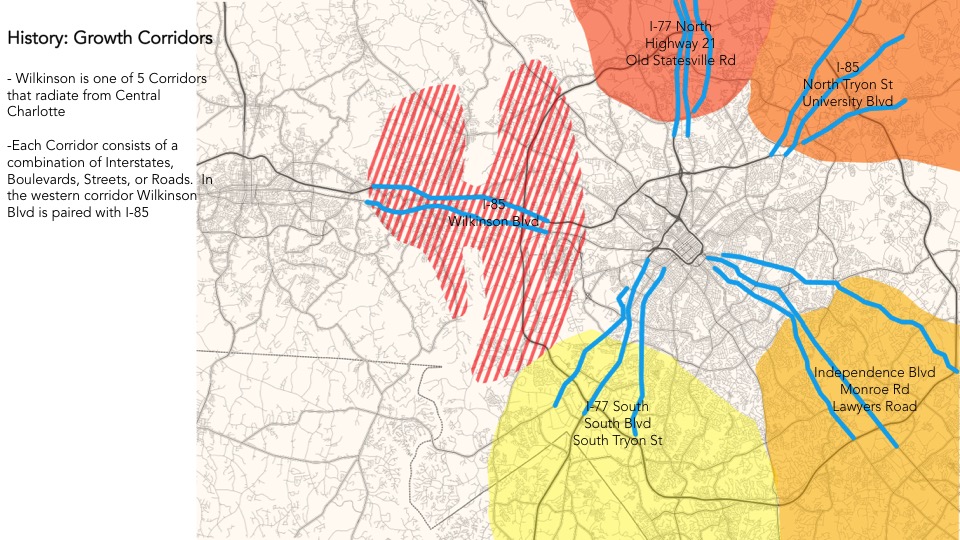

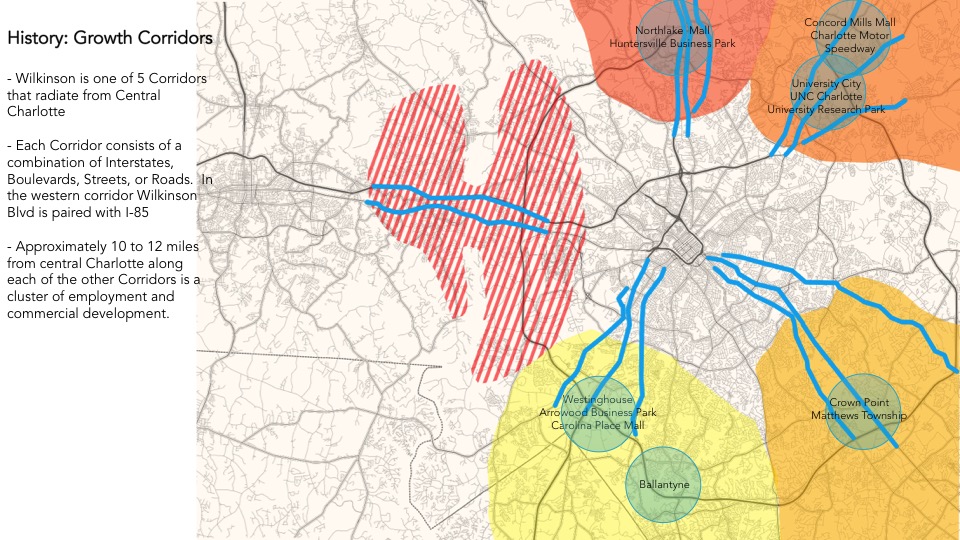

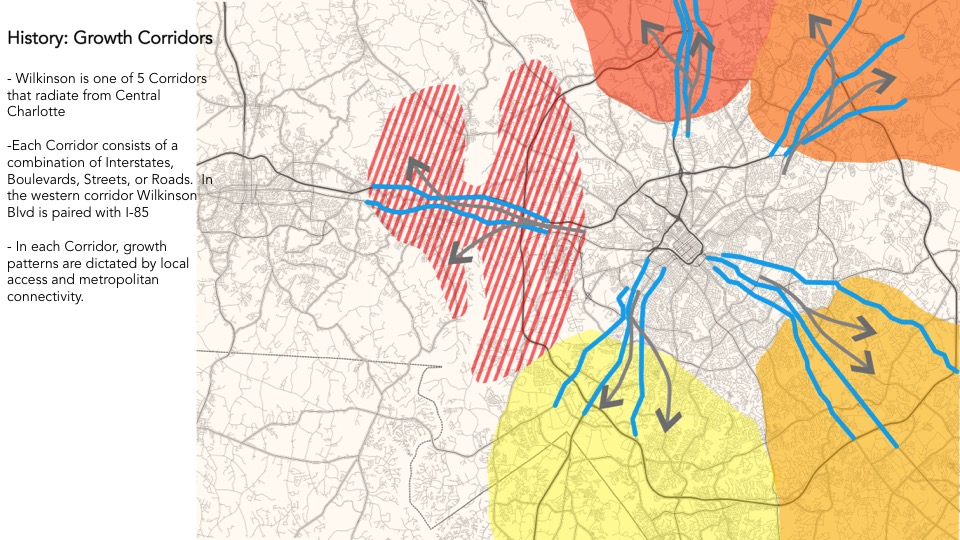

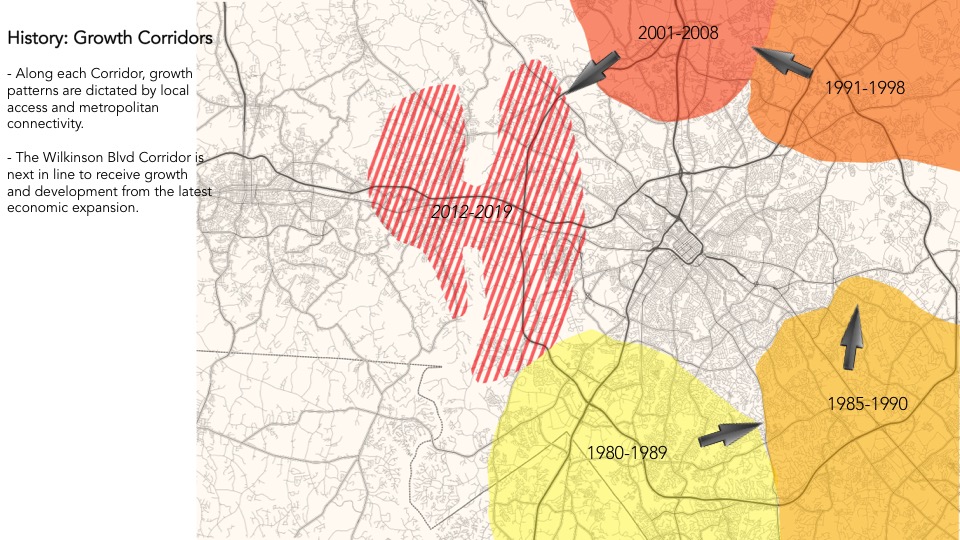

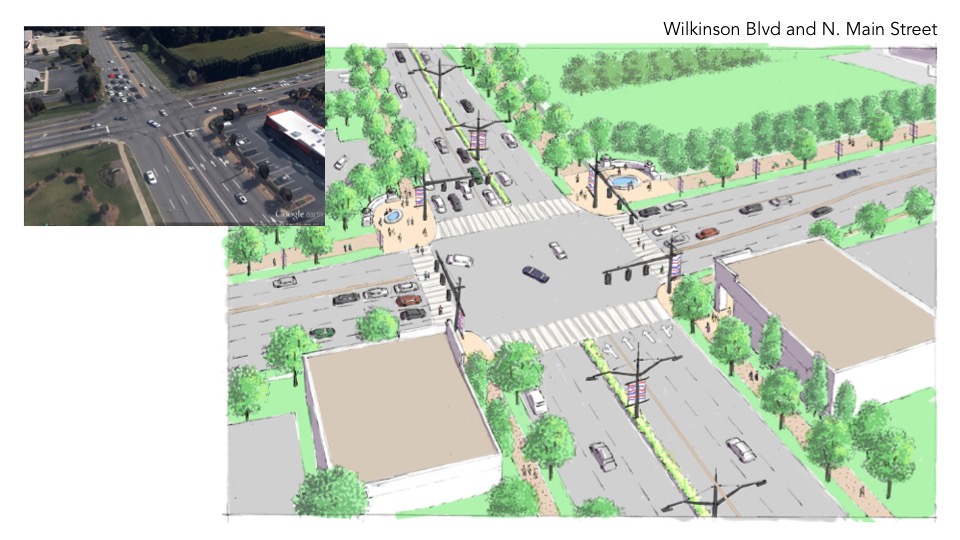

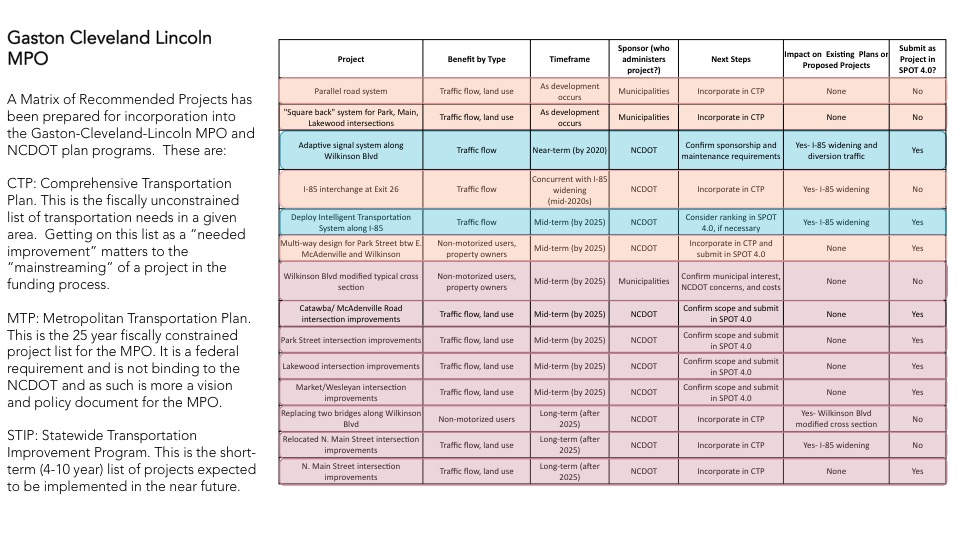

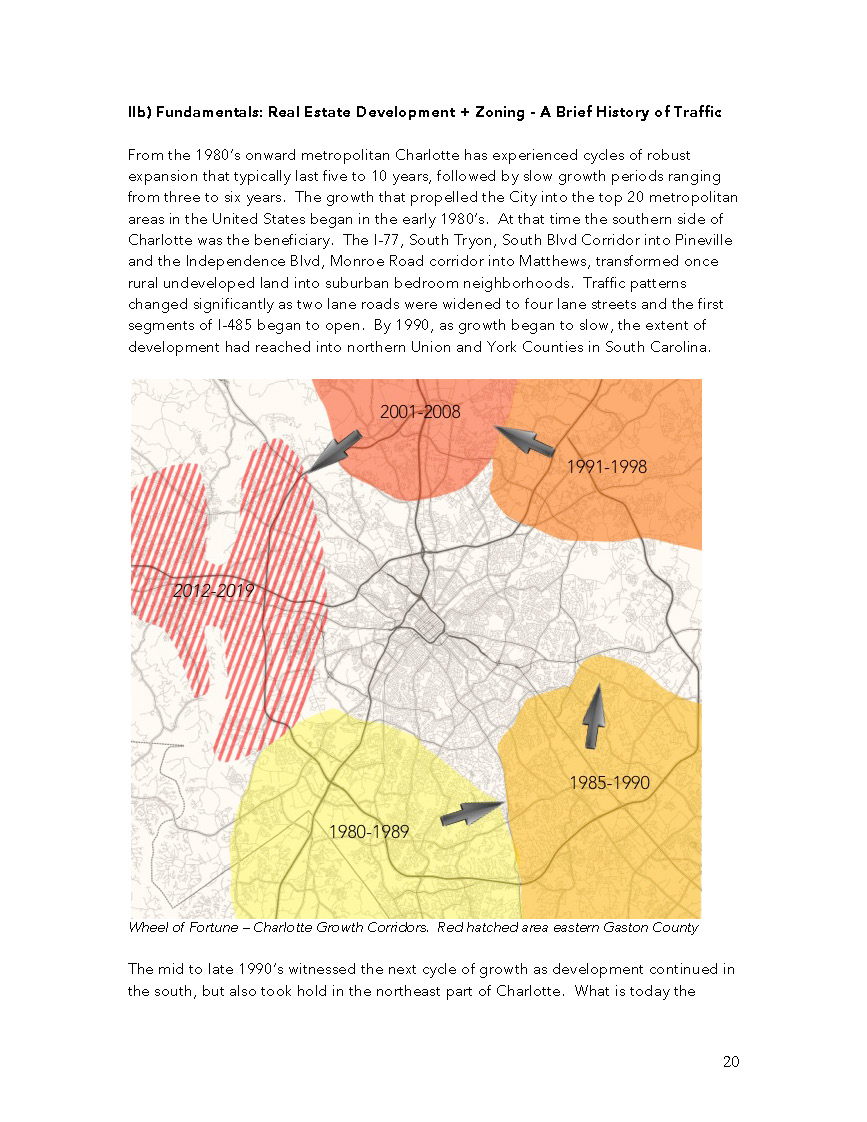

Together with local stakeholders and professional consultants, the municipalities of Belmont, Cramerton, and McAdenville are working to improve the quality of an important corridor that links the communities of eastern Gaston County and the greater Charlotte region. In studying the Past and evaluating the Present, we can create an informed and exciting vision of the Future role of Wilkinson Boulevard, one that continues to serve current and projected traffic needs while also encouraging new opportunities for residents and travelers.

The Presentation of Recommendations was given during a public meeting held on Thursday, January 15th at Cramerton Town Hall.

Please use the forward and back arrows above to view slides from the Presentation of Recommendations presented by the Team.

Please use the forward and back arrows below to view the Report of Recommendations provided by the Team.

CAPACITY VS. DEVELOPMENT

The Streets and Roads in our towns and cities were originally built to serve multiple functions.

First and foremost, they served to provide residents and visitors with a way to find homes and business. This was their initial and primary function: to establish addresses, around which people organized and located the daily needs of life. As more streets and roads were added to the community, they became the framework around which additional homes and business were built, creating the neighborhoods and downtowns of our towns and cities.

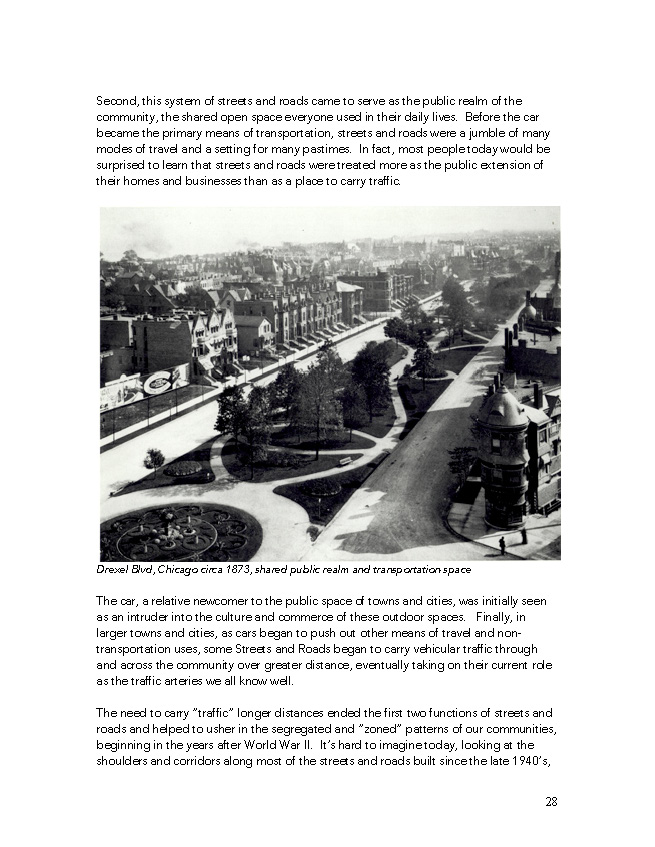

Second, this system of streets and roads came to serve as the public realm of the community, the shared open space everyone used in their daily lives. Before the car became the primary means of transportation, streets and roads were a jumble of many modes of travel and a setting for many pastimes. In fact, most people today would be surprised to learn that streets and roads were treated more as the public extension of their homes and businesses than as a place to carry traffic. A relative newcomer to the public space of towns and cities, the car was initially seen as an intruder into the culture and commerce of these outdoor spaces. Finally, in larger towns and cities, as cars began to push out other means of travel and non-transportation uses, some streets and roads began to carry vehicular traffic through and across the community over distance, eventually taking on their current role as the traffic arteries we are all familiar with.

The need to carry vehicular traffic longer distances ended the original two functions of Streets and Roads and helped to usher in the segregated and “zoned” patterns of our communities, beginning in the years after World War II. It’s hard to imagine today, looking at the shoulders and corridors along most of the streets and roads built since the late 1940’s, that these spaces use to be the predominant “open space” in most communities. People lived much of their outdoor lives along streets and roads; just ask anyone over 60 years of age. Before the war, streets and roads were contextually planned and purposefully built with ample sidewalks and/or landscaping, pedestrian scaled widths and easy access to adjoining destinations for people on foot and transit. They were “shared space” by design, busy and bustling places serving many different needs, for a while even including the newly arrived car.

As cars became the predominant mode of transportation in towns and cities, and as zoning developed to cater more to the requirements of car accessibility, Streets and Roads were forced to adapt.

This adaptation is reflected in the way streets and roads are now built, and how transportation engineering views their designs. No longer is context the main determinant of design. Instead capacity is now the primary function of any street or road, with capacity determined by the number of vehicles that can travel in a given peak hour. The complexity of the Streets and Roads system that developed over thousands of years has, in the past half-century, been completely reduced to reflect a hierarchy of simple attributes.

Today’s transportation engineering modeling uses three classifications of thoroughfare: arterials, collectors and locals. Traffic flow, especially through or around potential points of congestion, is the main driver of street and road design. The underlying goal of these designs is safety, and as a result, every new road -- whether in the country, the suburbs, or the city -- has the same design features.

Traffic flow and safety are well intentioned. However, once safety is accounted for on major corridors like Wilkinson Boulevard, there is confusion as to what the streets and roads of Belmont, Cramerton, and McAdenville are suppose to actually do for residents and visitors. This confusion is especially apparent when Wilkinson Boulevard is the topic of discussion, as witnessed by the public input at the recent workshops and discussions on the Build a Better Boulevard Facebook page.

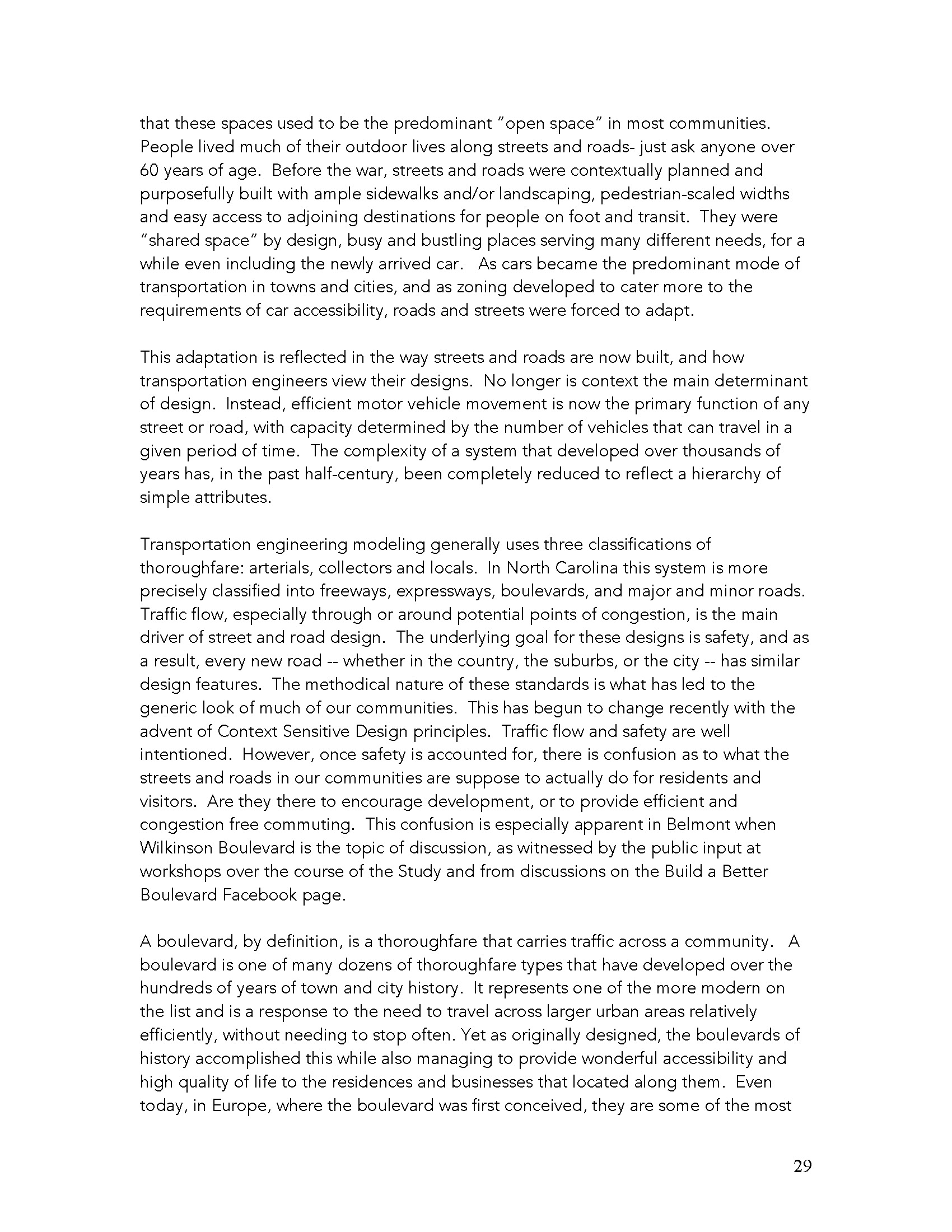

A Boulevard, by definition, is a thoroughfare that carries traffic across a community. A boulevard is one of many dozens of thoroughfare types that have developed over the hundreds of years of town and city history. It represents one of the more modern thoroughfare types and is a response to the need to travel across larger urban areas relatively efficiently without making frequent stops. Yet as originally designed, the Boulevards of history accomplished this while also managing to provide wonderful accessibility and quality of life to the residences and businesses located along them. Unfortunately, in the past half-century many urban boulevards have typically been stripped of their multi-use complexity, only serving to funnel traffic, through a community and on to other destinations.

This raises the obvious question of “through to where”?

If “through traffic” is the main goal, then the ideal boulevard would function more like the even newer Interstate system, with no disruptions and limited access points controlled by interchanges. To support this restricted access design intent, changes to zoning would also need to be made, restricting growth along boulevards. In theory this is the case for interstates; they aren’t designed to encourage development either. Each new development creates the need for access points and the congestion that follows, a scenario that defeats the purpose of building an interstate to begin with.

However, as we all know through observation, streets and roads and even interstate highways are great generators of development in populated areas, especially those with high traffic volumes. One only needs to look at the Charlotte Outer Loop or the Atlanta Perimeter to see the folly in the idea that urban Interstates can simply “bypass” congestion. Not yet completed and after a generation of construction and over a billion dollars spent, Charlotte’s Outer Loop is already being rebuilt to accommodate the growth and development it has generated. The experience of other metropolitan areas shows that such “rebuilding” will continue unabated for decades to come and at the cost of more billions.

Returning to Wilkinson Boulevard, if this corridor is only supposed to carry traffic through to other places, what happens to Belmont, Cramerton and McAdenville? Are these communities the unfortunate obstacles in the flow of cars trying to travel between Charlotte and Gastonia? Or instead, is everyone traveling the corridor made to suffer delays in their commute on Wilkinson Boulevard because of what a great places Belmont, Cramerton and McAdenville are and want to continue to be?

In the Build a Better Boulevard workshops, we heard arguments for both alternatives. Some wanted to see more development along Wilkinson Boulevard and an increase in traffic along the corridor because they see the gradual decline businesses as a drawback to the image and economy of the area. Others want to take the design of the Boulevard in the direction of a limited access highway, reducing the opportunities for businesses to locate along the corridor in order to maintain speed and flow of traffic across the Peninsula’s communities.

Whose argument is correct?

Just as with the previous discussion concerning traffic congestion and speed, the answer is: both are. Through a bit of “Town Whispering” we can discover the best solutions, based on both the original intent of Boulevard design and the current situation of the transportation system, and we can apply the findings to “build a better boulevard” out of Wilkinson.

So what do we know?

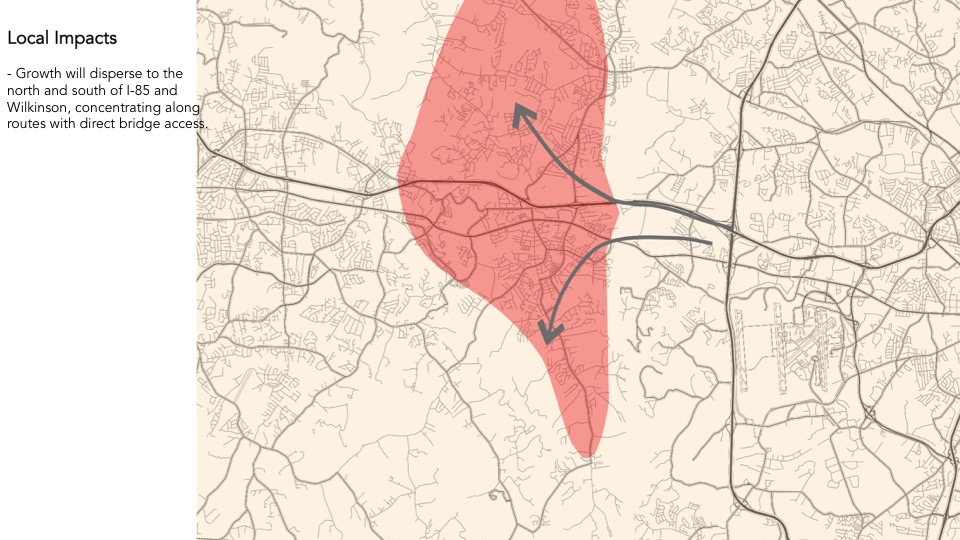

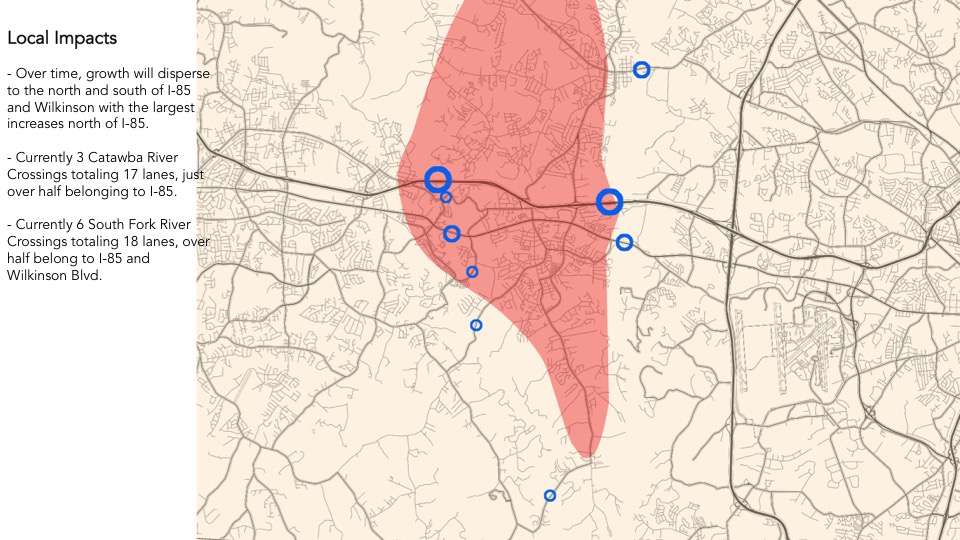

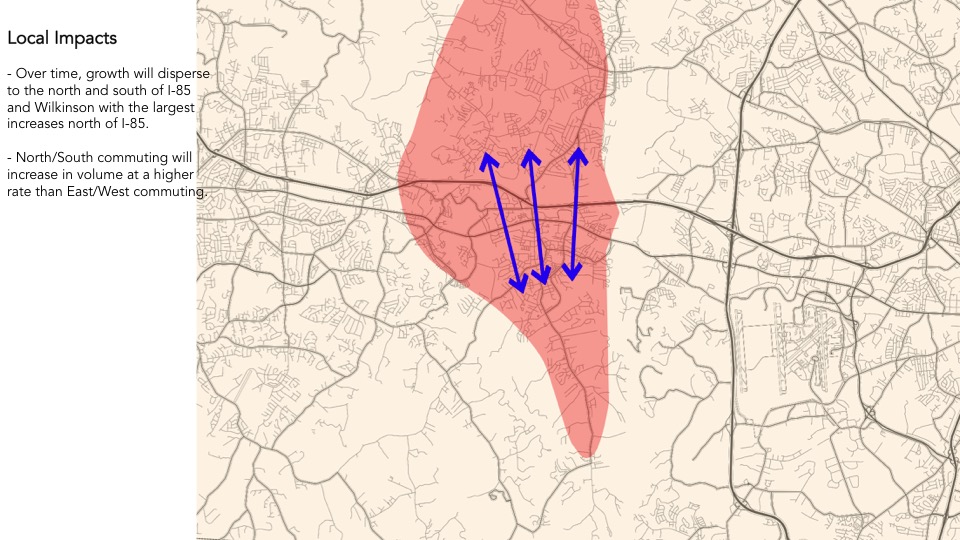

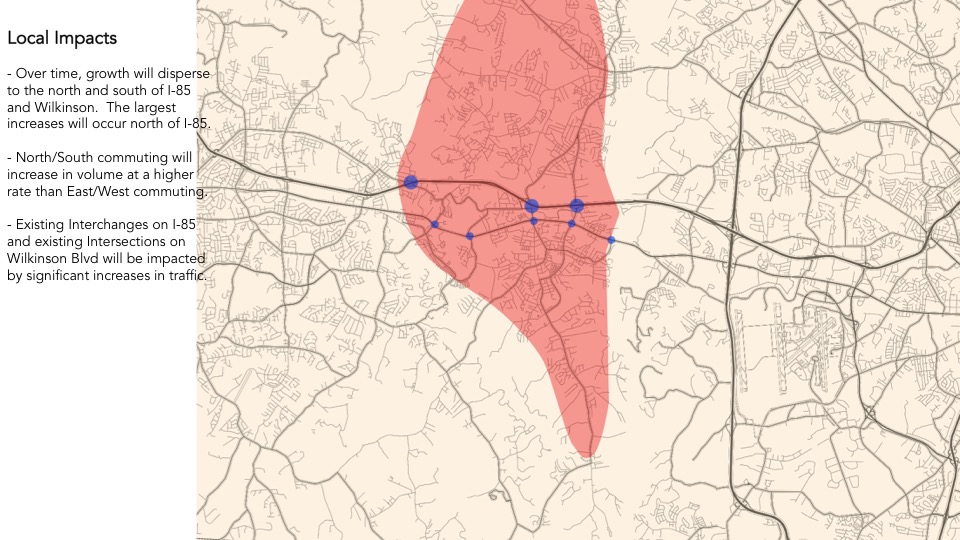

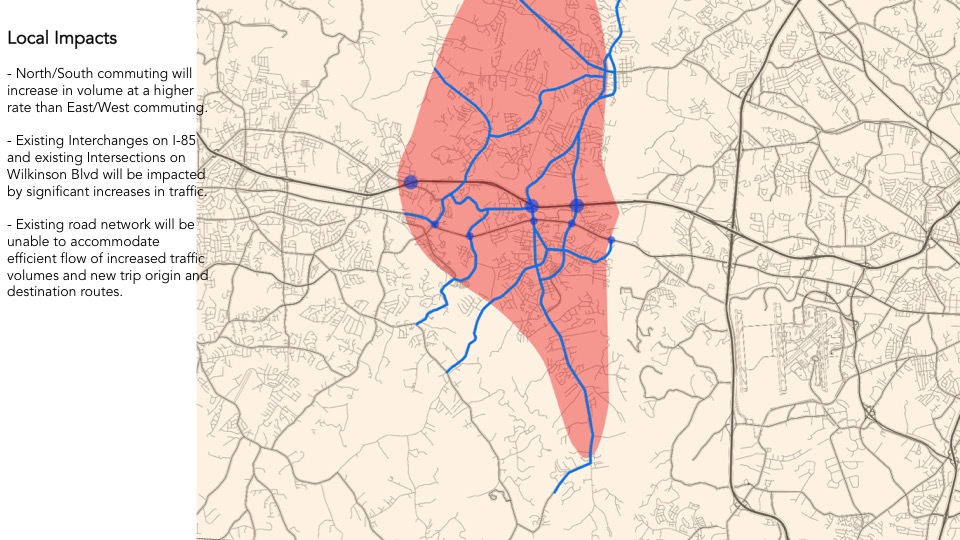

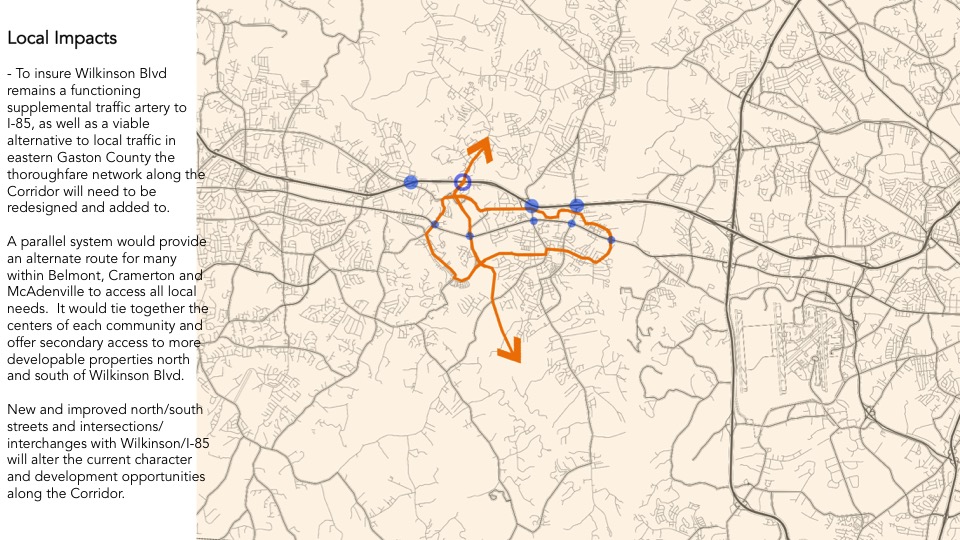

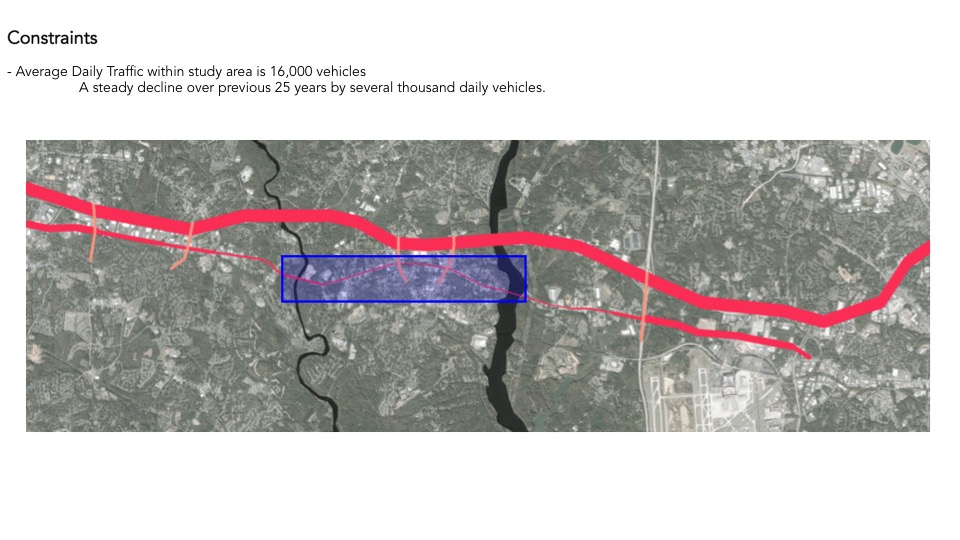

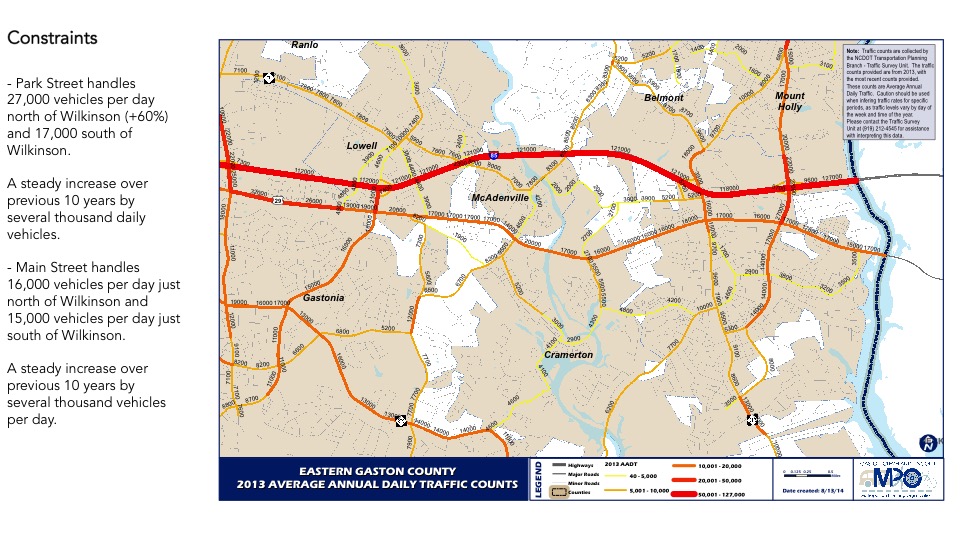

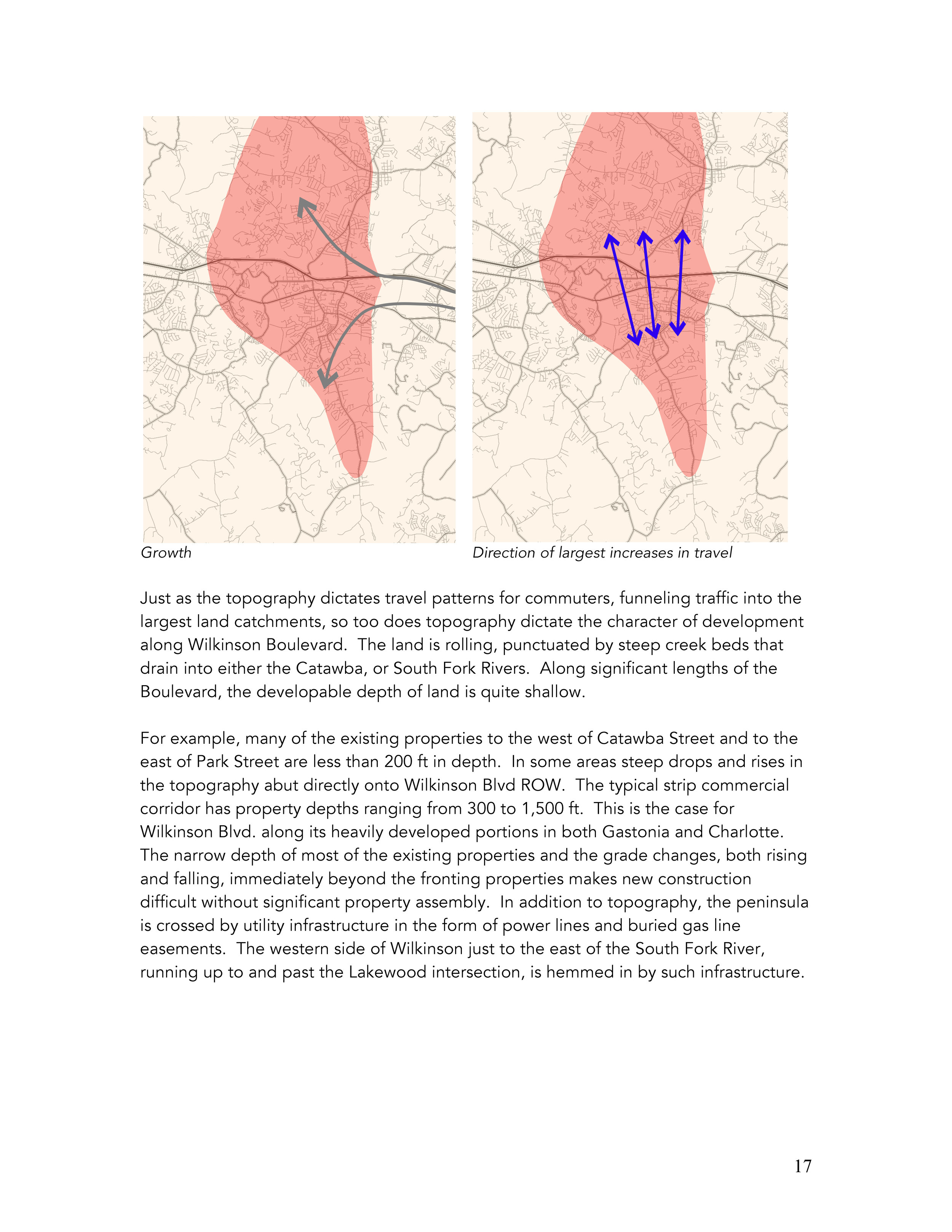

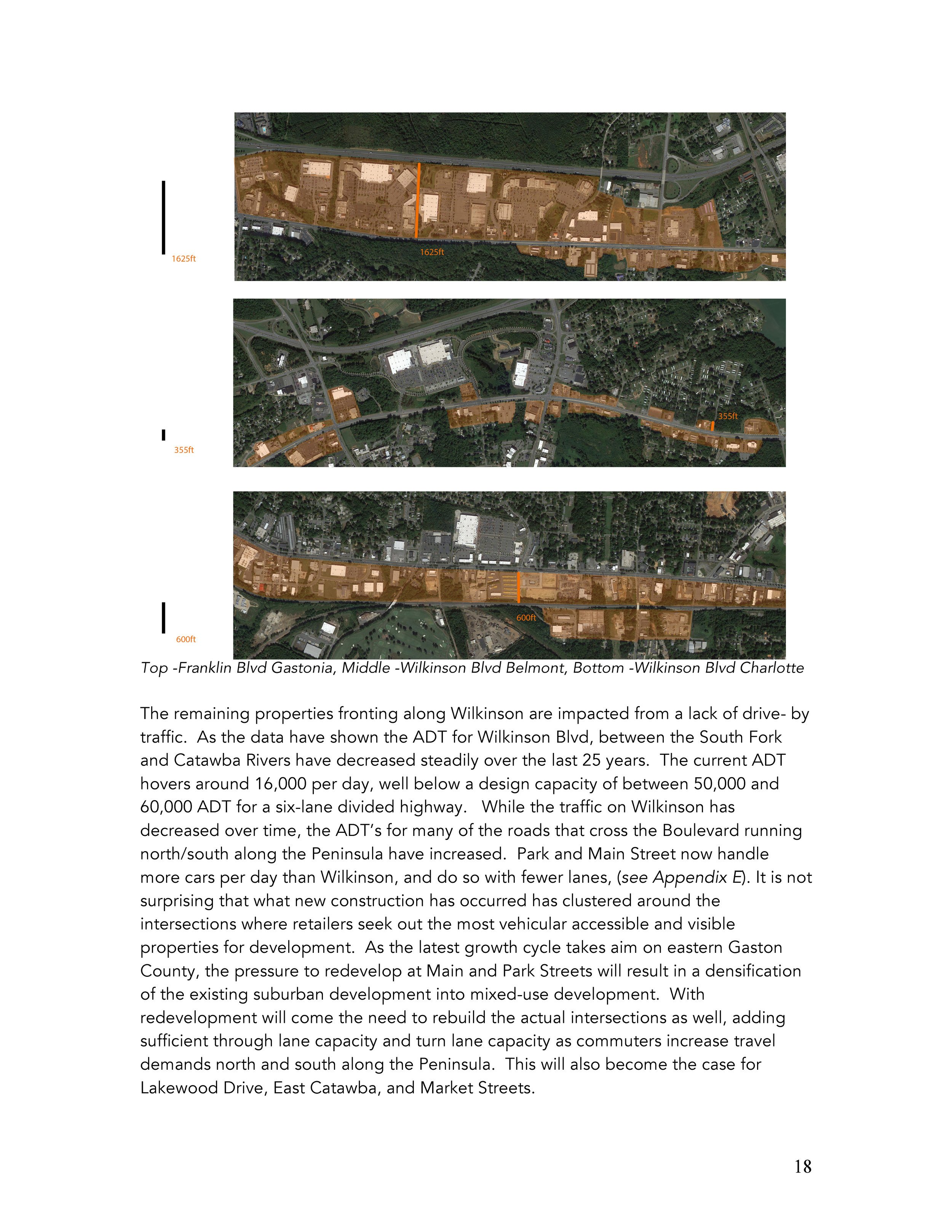

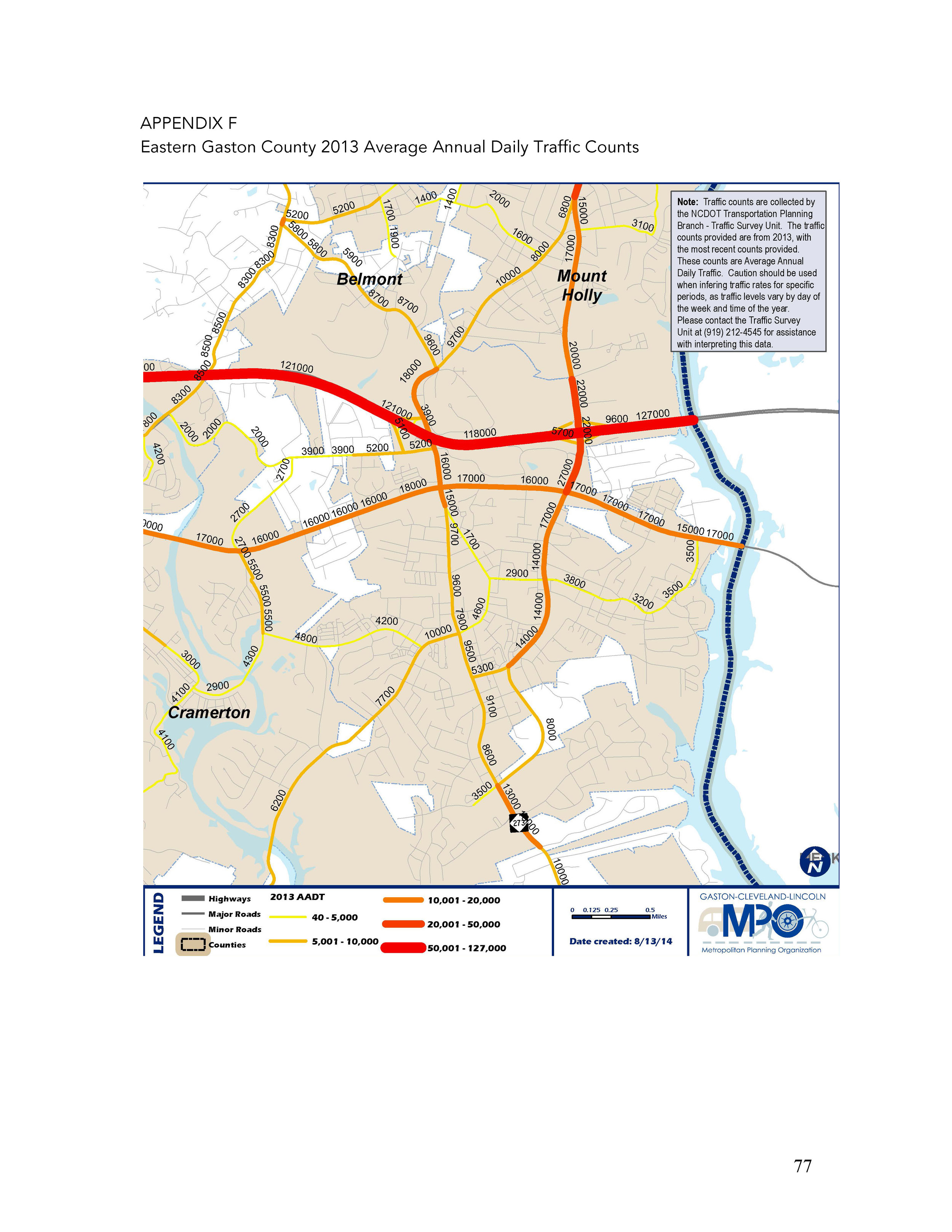

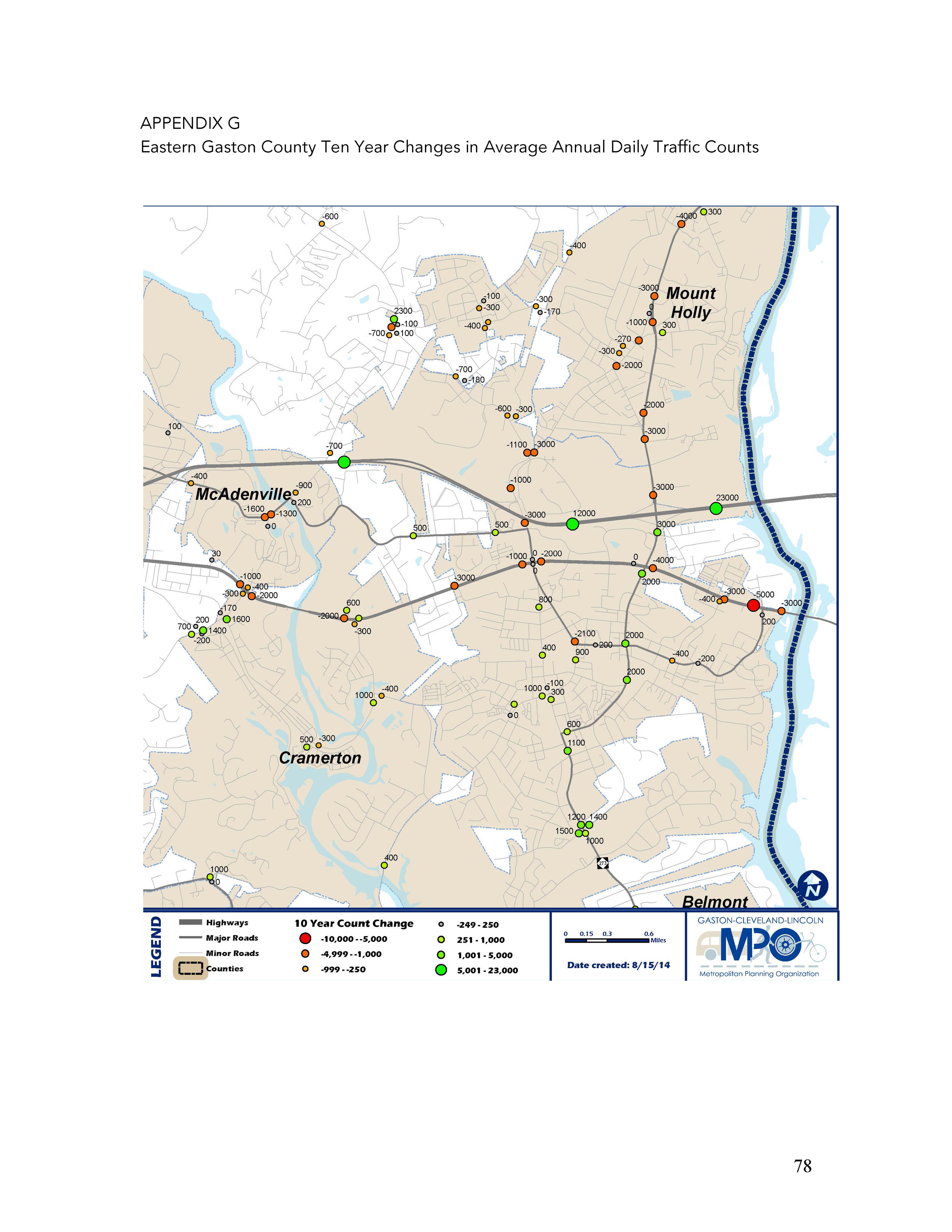

We know that the existing traffic counts are much lower on Wilkinson Boulevard than its design capacity. We also know that the largest increases in Average Daily Trip (ADT) counts are occurring on the north-south thoroughfares crossing Wilkinson Boulevard. It is at these intersections where most of the new business development along the corridor has occurred. The areas where businesses seem to struggle are farther away from these intersections. Fortunately, the intersections are evenly spaced and there are few relative to the length of the corridor so that even during peak hours, traffic is able to stagger as it flows through Belmont, Cramerton and McAdenville. Given their faster growth and similar traffic counts, the north-south thoroughfares have become and will continue to be prime frontage for development investment.

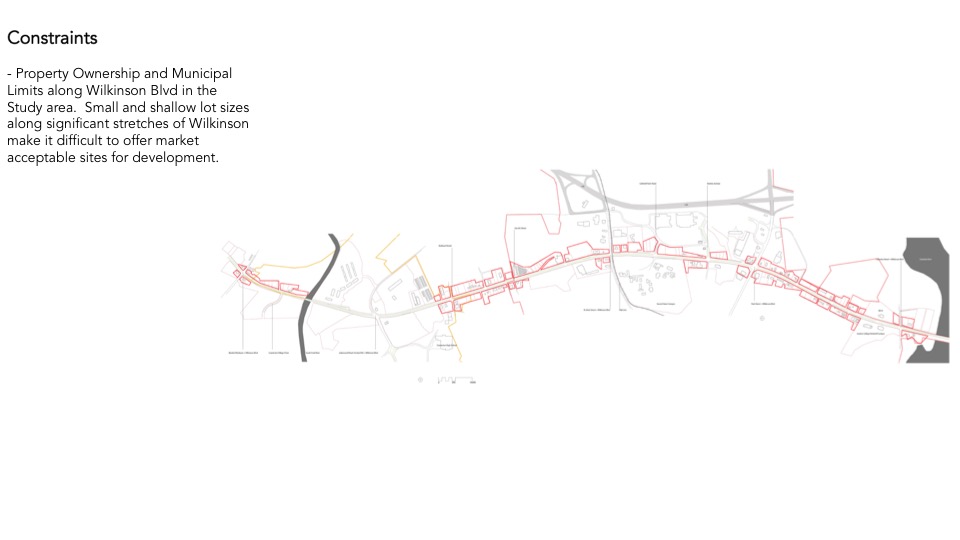

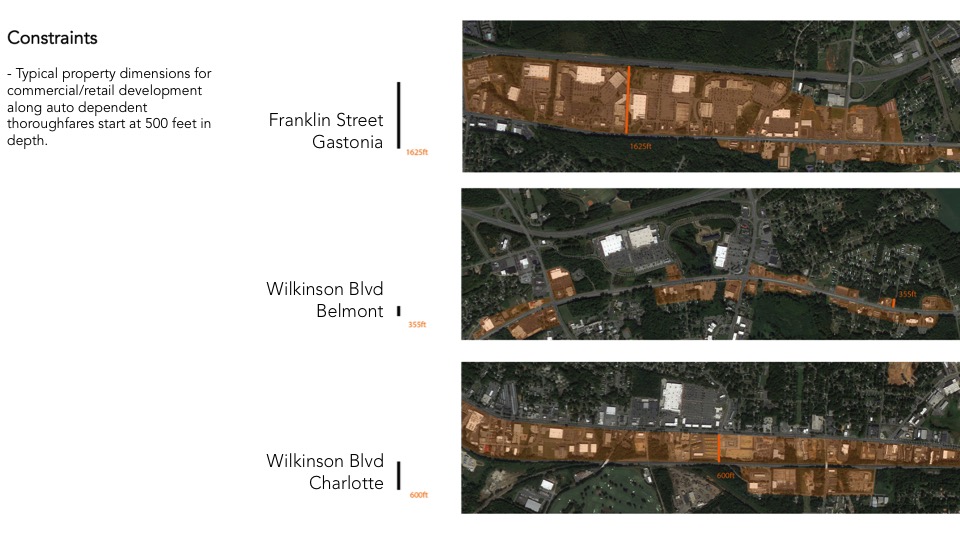

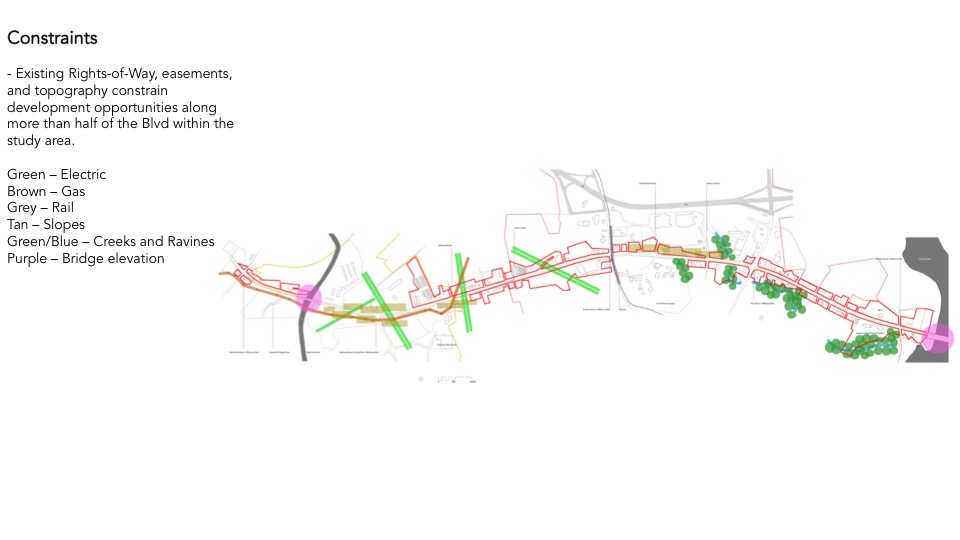

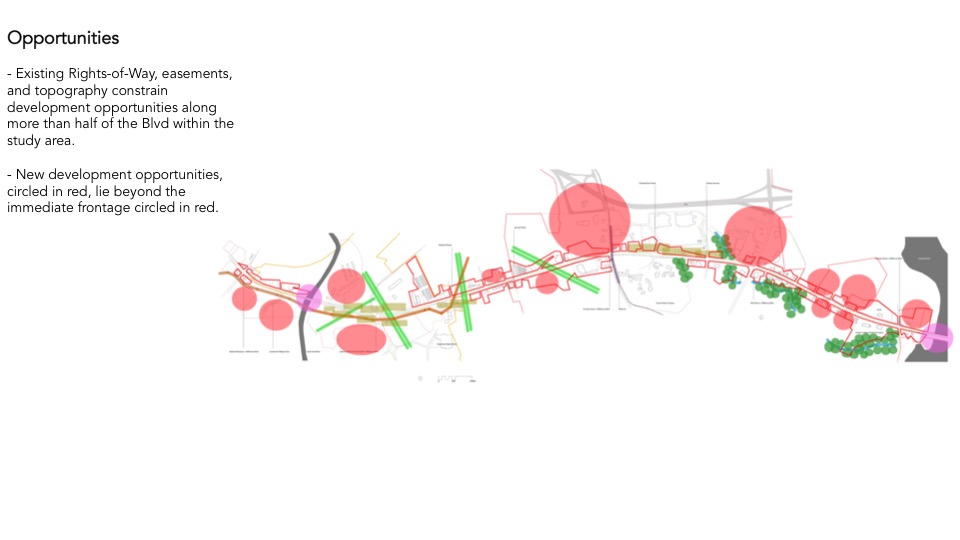

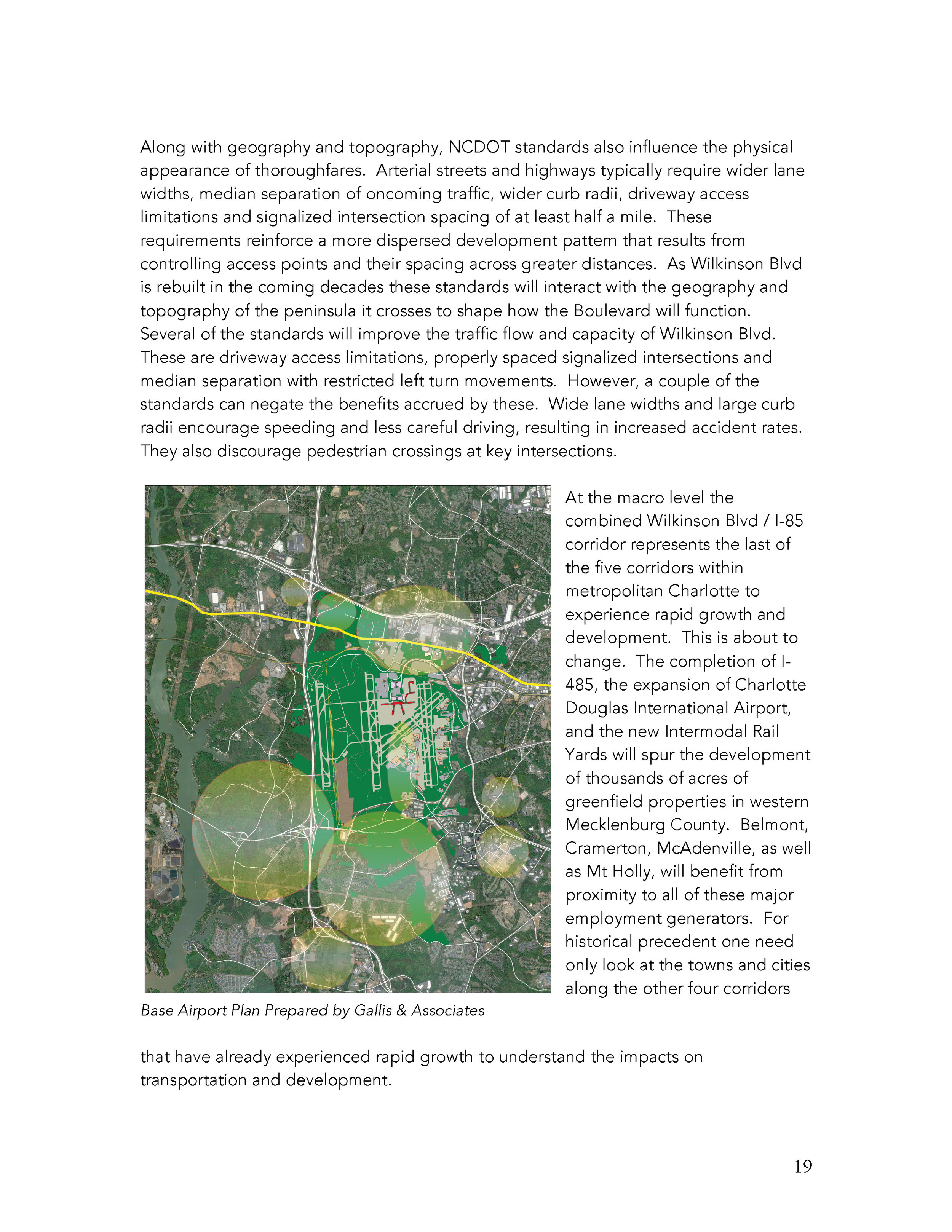

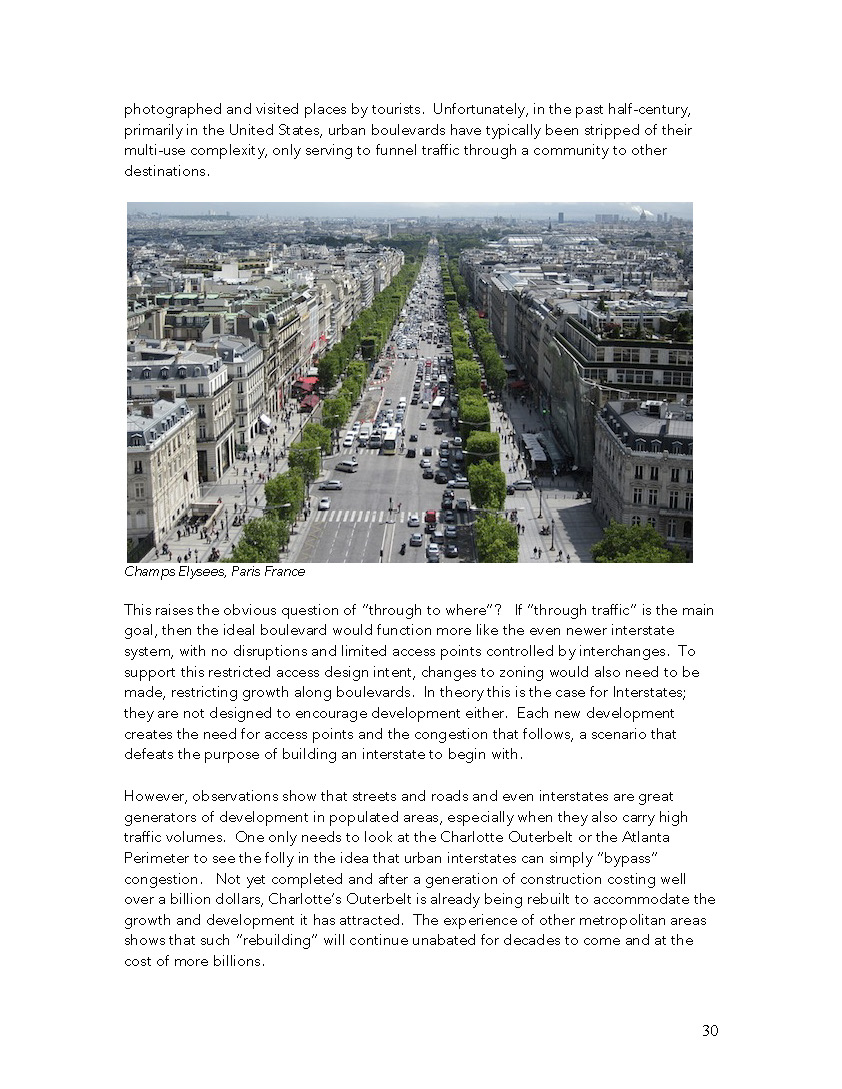

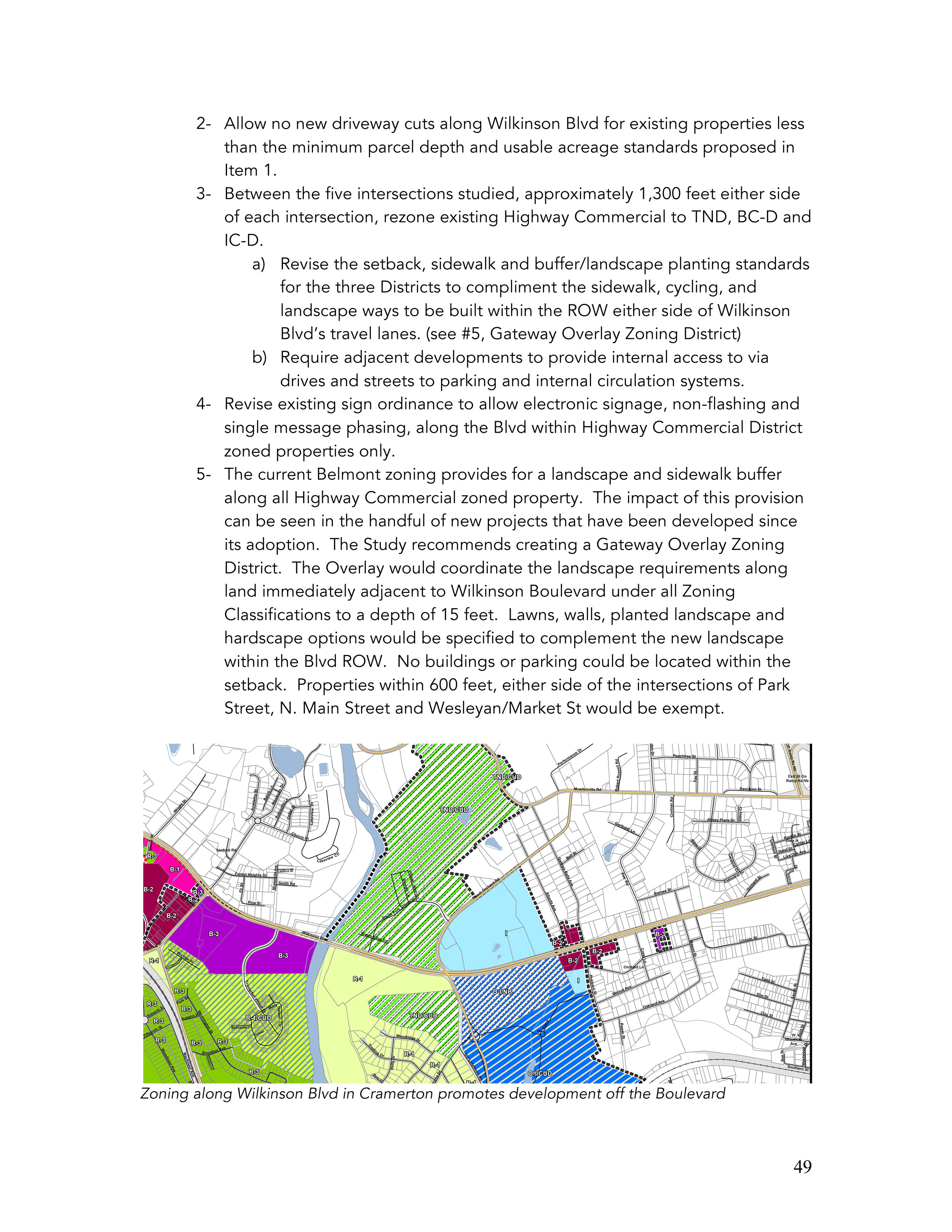

In addition to traffic counts, the available land and its parcel assembly is also greater on the north-south thoroughfares than what is available along Wilkinson Boulevard. The depth and size of most properties, the topography associated with creeks and drainage areas, and the adjoining rights-of-way and easements make most of the Wilkinson Boulevard corridor difficult to develop. Property assembly takes time and can be costly. As development pressure increases due to growth outward from Charlotte, land assembly will begin to make economic sense. When initiated, these new projects will take advantage of the larger parcels, developing away from the immediate boulevard frontage, internalizing commercial and residential development within their sites and leaving Wilkinson Boulevard frontage to accommodate landscaping and offer fewer driveway access points. This can already be witnessed in Cramerton, at the new Southfork Village Apartments, as well as projects on the drawing boards immediately surrounding this new development.

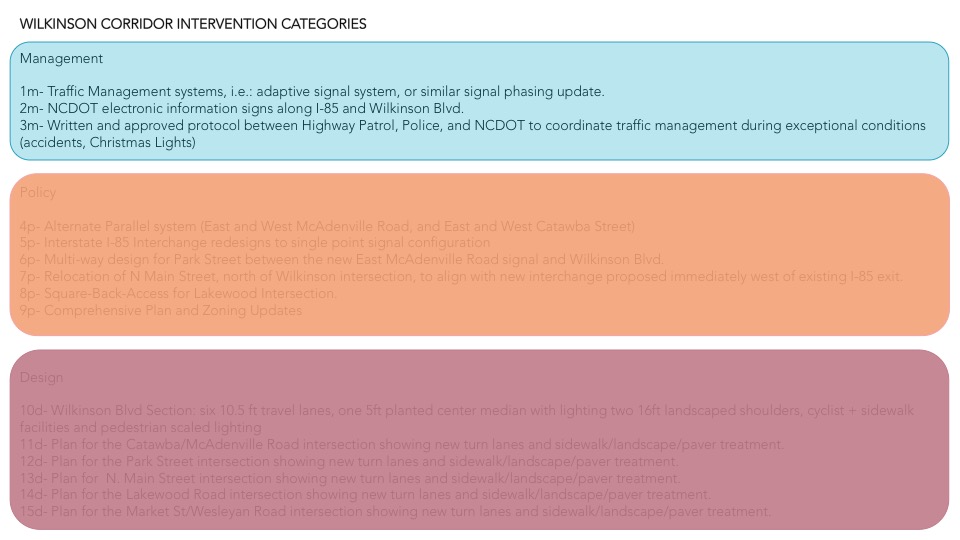

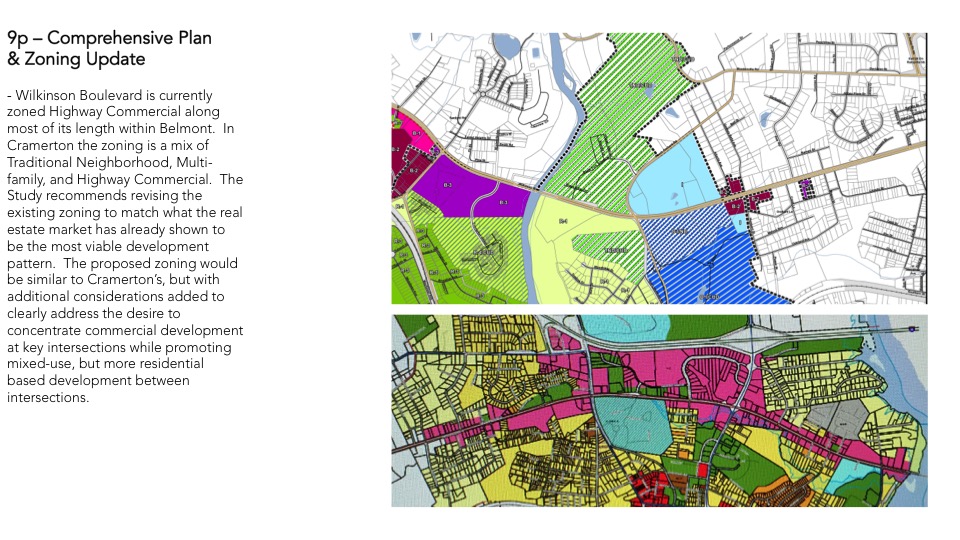

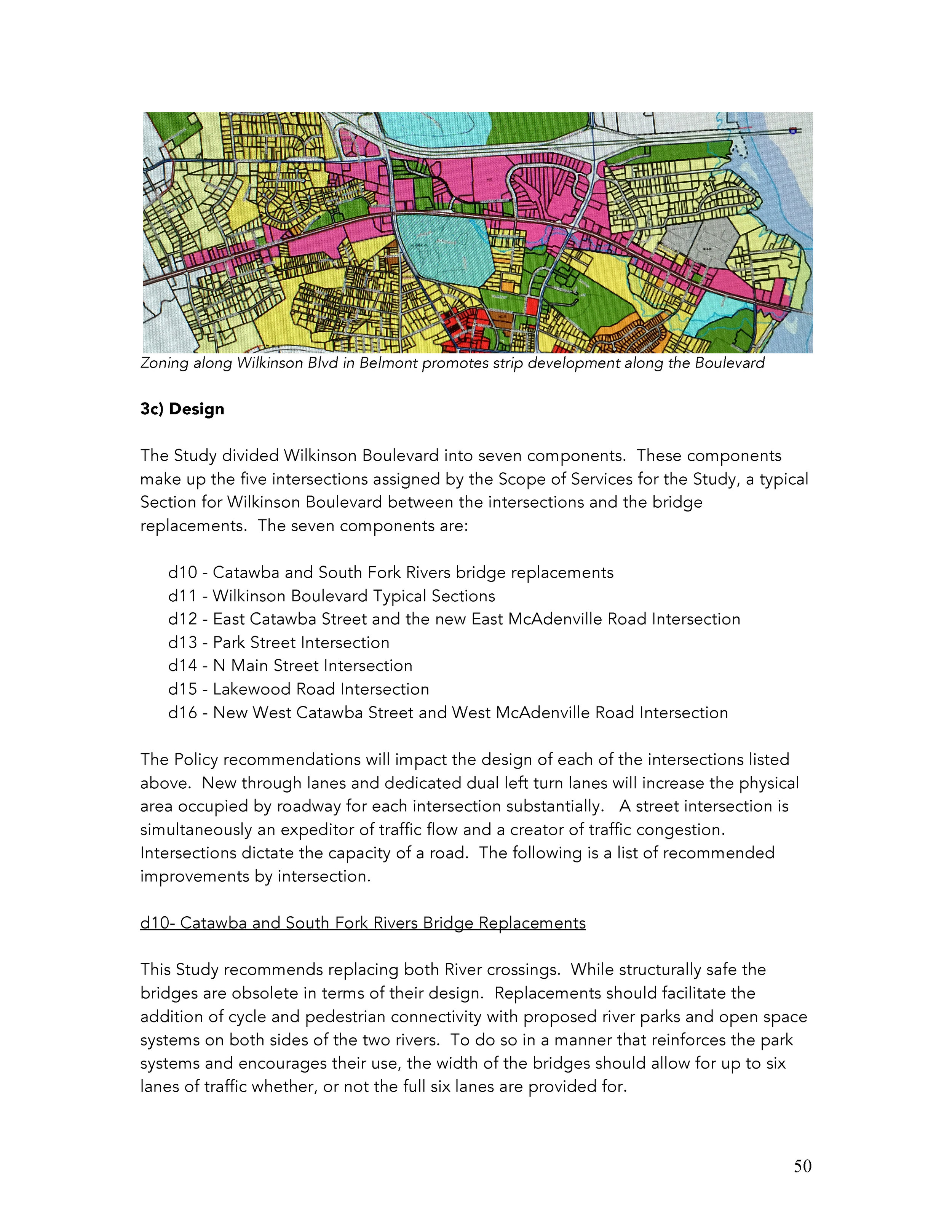

Comprehensive Plan updates and Zoning changes should be put in place to facilitate this market-driven change, complimenting the beautification of Wilkinson Boulevard proposed by the aesthetic recommendations of the boulevard study being prepared. Doing so will also promote better traffic management. How? By concentrating busy commercial hubs at the major intersections, car trips accessing them can use I-85, Wilkinson Boulevard, and the north-south thoroughfares themselves. This concentration also encourages developments to become mixed-use, reducing the number of driveway cuts needed along both Wilkinson Boulevard and the north-south road system. With additional zoning changes, these new projects will be designed to promote a park-once-and-walk environment, reducing total car trips along the corridor.

By reducing the need for Wilkinson Boulevard to be the business corridor for the Peninsula’s communities, the corridor can be freed up to serve as a regional connector. New business development can be focused at intersections along the corridor and, more importantly, in the downtowns of Belmont, Cramerton and McAdenville. This will also allow for the beautification of Wilkinson Boulevard, creating the better community image sought after by residents. After all, why spend money on beautifying a corridor if all that is developed immediately behind the landscaping are chain restaurants and parking lots? Wilkinson Boulevard and the Peninsula’s communities want to aspire to more than that.

Written by Demetri Baches AICP, ULI, CNU-A of Metrocology, Inc.